The Book of the Courtesans, Part 1: Marthe Aguillon

In the archives of the Paris police, there is a book. It is large and heavy, with a worn leather binding, brass hardware, and a broken lock. It contains the criminal files of a group of women called Les Insoumis— “the Undominated.” These were women who lived their lives outside the bounds of polite society, but who refused to register as prostitutes. Most were not selling sex on street corners or working in brothels. They were the mistresses of dukes and princes, or even of princesses. In return for their favors, they might receive not money, but an apartment near the opera house, or a small country villa. Some were actresses, some dancers, some world-famous comediennes, while others still were playwrights or journalists who concerned themselves with a dangerous new concept: feminism. All of them, the vice squad decided, were “courtesans” and must therefore be surveilled. This secret ledger, known as The Book of the Courtesans, or by its code name “BB1,” survived a siege, a revolution, the 1871 burning of the archives, and two world wars.

BB1 in the Paris police archives. Photos by me.

In 2006 it was transcribed and published in French with annotations but no illustrations, by renown historian Gabrielle Houbre. In 2016, while researching my forthcoming book The Parisian Sphinx, I was able to see the original document and its pasted-in photographs for the first time. Beginning with the files as presented, I began to reconstruct the lives of these remarkable women by searching for them in 19th century newspapers, photo archives, and civic records, treating them not just as cultural phenomena or historical color, but as individuals.

These are their stories.

One: Marthe Aguillon

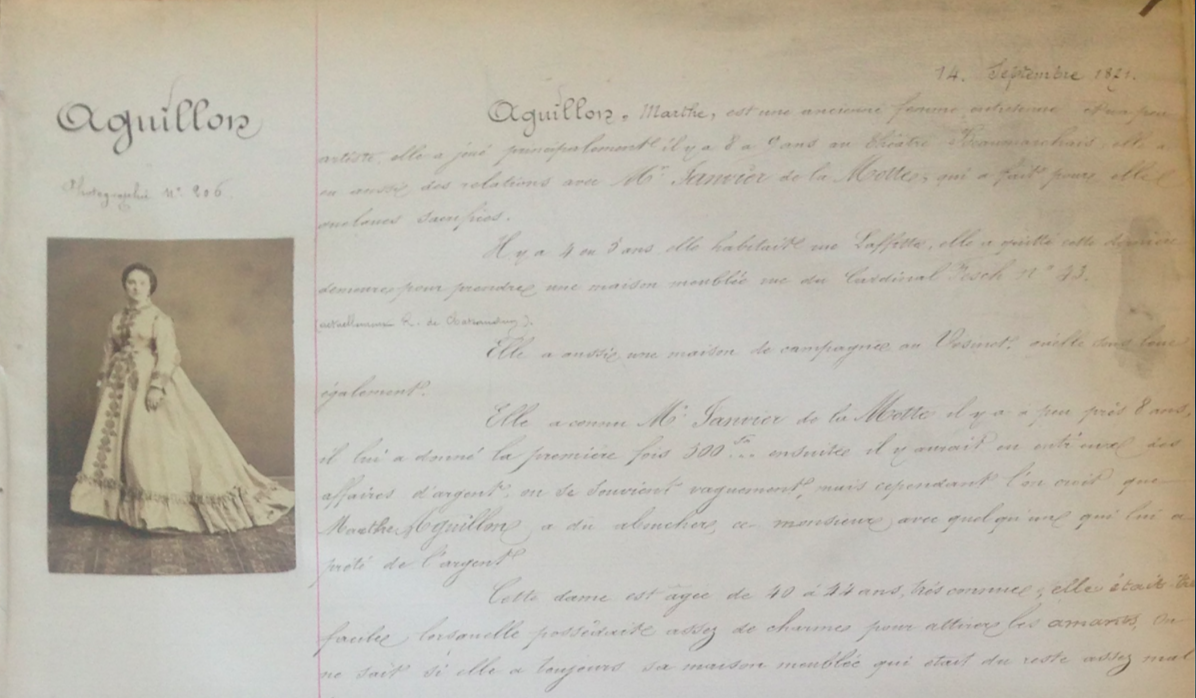

“Marthe Aguillon” in BB1. Photo by me.

THE FILE

September 14, 1871

Aguillon, Marthe

The first thing they had to say about her was that she was well-kept, “somewhat artistic,” and very famous. She was an actress, between forty and forty-five years of age, and had spent the past decade or so performing at the Théâtre Beaumarchais near Place de Vosges. During this time, she also “had relations” with one Monsieur Janvier de la Motte, who, for her benefit, had “made some sacrifices” (a euphemism, no doubt, for considerable money spent).

Four or five years ago she lived on the rue Lafitte, but then moved to a furnished house at 43 rue du Cardinal Fesch (now rue de Châteaudun), near the church of Notre Dame de Lorette, in the comfortable 9th arrondissement. She met M. Janvier de la Motte some eight years prior, at which time, they said, he gave her five hundred francs. The police believed she met him through another person who had loaned her money.

She was “very easygoing” when she possessed enough charm to attract lovers, the police said. They didn't know if she still had the furnished house, which they'd found to be “rather poorly maintained.” She now lived on the rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette.

There were no further notations.

THE RESEARCH

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Nadar, c. 1865. Musée Carnavalet (source).

“The two green room doors had been left wide open to the passage leading backstage. Figures were dashing past along the yellow wall, brightly lit by an invisible gas-lamp: men in costume, half-naked women wrapped in shawls, all the second-act extras, the riff-raff for the shady dance-hall...and at the end of the passage, people could be heard clattering down the five steps which led to the stage.”

Her real name was Marthe Léocadie Baumann.

She was born around 1830, the year when Paris convulsed with the violence of the July Revolution. In the city, there was chaos. Revolutionaries sacked the Tuileries Palace and raided the royal wine cellars. One man located a ball gown belonging to the Duchess de Berry, put it on, and with feathers and flowers in his hair, screamed out of the palace window into the gardens below “Je reçois! Je reçois!” (“I receive! I receive!”).

Marthe spent her childhood under the rule of the last king of France, the Orléanist Louis Philippe, only to see him overthrown and replaced in yet another bloody revolution by Napoleon III around the time she came of age.

She started using the stage name “Aguillon,” perhaps to hide a Jewish or German heritage, by as early as 1861 when she made her debut in the press. As an actress, the critics called her “well traveled.” She performed at many respected theaters all over Paris, including the Théâtre Beaumarchais, the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, the Dejazet, the Boulevard du Temple, the Gaîté, the Théâtre-Montparnasse, and the Théâtre-Molière in Brussels.

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Louis Alexandre Dalligny. Musée Carnavalet (source).

She was a serious actress, praised in rave reviews for her talents, but she could also handle comedic roles. “Here is a very great lady,” wrote one critic in Le Figaro in October of 1865. “With comedic actresses of this caliber, a play is saved.”

In one production written by the female playwright D. Rouy, she portrayed a young Italian man named Stephano, a hero who seduces the heroine. “She gives the role of Stephano a cachet of distinction, that contrasts singularly with her mania for landing journalists in court,” Le Figaro wrote, suggesting that she may have responded litigiously to gossip and slander.

Left: Théâtre Beaumarchais, illustration. Right: Promotional poster from the Théâtre Beaumarchais. Both courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Etienne Carjat. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Photos by me.

Her glory days appear to have been in the 1860s, when she was in her 30s and early 40s.

“A brilliant artist, already crowned with success,” said La Comédie in 1864. “Well framed and perfectly played,” the Revue Artistique et Littéraire said of her performance in La Louve de Florence at the Théâtre Beaumarchais in 1865. The next year in 1866, the same journal declared the drama The Black Band, also at the Beaumarchais, to be “full of dread and well-played, especially by Marthe Aguillon.” When she performed at the Théâtre-Montparnasse, L'Europe proclaimed her role to be “played with zest and remarkable feeling, if a little exaggerated...a little bit more calm and measure and Madam Aguillon will find her path.” The Tintamarre wrote that she was “dramatic, with sparkle” and that she had a sparkling voice, elevating the actors who performed alongside her. By 1870, the year before the vice squad declared her to be a courtesan, the newspaper La Pays said that she was on the same level as Sarah Bernhardt:

“Actresses ignite. The day before yesterday, it was the gracious Sarah Bernhardt, at the Odeon: yesterday, it was the plump Berthe Legrand, at the Variétés: today, it is the brunette Marthe Aguillon.”

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Felix Nadar. Left: Musée Carnavalet (source). Right: Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Photo by me.

Marthe was financially successful in her prime, and it showed. She dressed in fine clothes, and had her picture taken by the most famous photographers in Paris. A photo of her with a top hat and riding crop may indicate that she was an equestrienne, as a number of demi-mondaines of her era were, setting out for long rides in the leafy Bois de Boulogne. She had light eyes, a petite rounded frame, and her hair cascaded down her back in shining brown ringlets that reached to her corset-cinched waist.

French evening gown, c. 1867. Metropolitan Museum of Art (source).

French day dress, c. 1867. Metropolitan Museum of Art (source).

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Charles Reutlinger. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Photo by me.

Eugène Janvier de la Motte, by Franck. Musée Carnavalet (source).

When she met Eugène Janvier de la Motte in 1863, he was 40 years old and legally separated from his wife. Mme Janvier de la Motte had left her husband after discovering him in the arms of an actress at the Hôtel de l'Europe. (He would prove to have a thing for actresses.) She obtained her independence in 1861, then died in 1865, leaving him free to remarry if he so wished. He did not. By the time that he and Marthe were introduced—perhaps, as the police suggested, through an intermediary when she felt that her debts had grown too difficult to manage—he was the state representative of Eure, a department to the northwest of Paris. He nevertheless spent plenty of time in the city, and was already legendary as a thrower of lavish parties and a giver of generous grants, acquainted with the likes of Victor Hugo and Jules and Edmond de Goncourt. Now a merry widower, he was known for maintaining several actress mistresses at once, and for organizing orgiastic soirées at the Grand Hotel with as high a class of ladies as he could convince to attend. Naturally, he also made enemies. By 1867 the prefecture he managed was in a tremendous amount of debt, to the tune of 700,000 francs. Following an altercation with a member of the General Council, whom he slapped in the face, he was fined 3,000 francs. He was then sent to represent the prefecture of Gard along the Riviera in 1869, and in 1870, fled France to escape the Franco-Prussian War by hiding out in Switzerland. When the new French government took office after the quelling of the Paris Commune, a warrant was issued for Janvier de la Motte’s arrest. Over 110,000 francs of his prefecture’s funds had gone unaccounted for, and he was accused of embezzlement. He was apprehended in Geneva in August of 1871—interestingly, just one month before Marthe’s appearance in the Book of the Courtesans—extradited to France, and sent to prison in Rouen to await trial. However by January of 1872, just a few months later, he was acquitted on the testimony of the Minister of Finance himself, causing such a scandal that the minister was later forced to resign.

The trial also exposed to the public his debauched and extravagant lifestyle, which despite providing salacious fodder for the press, did not seem to hurt his career aspirations or his personal life in the slightest. On the contrary, he went on to found a newspaper, win election as the deputy leader of the Bonapartist party in Bernay, and eventually obtain a seat on the General Council of Eure, his old prefecture, which he maintained until his death. The son he had with his late wife went on to become a political figure. He continued to keep various actresses as mistresses, and fathered another child with the actress Henriette Renoult. He died in Paris in 1884 at the age of 60.

As for Marthe Léocadie Baumann, aka Marthe Aguillon, the last we hear of her in the press is in 1888. By then in her late 50s or early 60s, she was performing as a comedic singer in Brussels, still working under the same stage name, still entrancing audience with her sparkling voice.

I tried very hard to find out what finally happened to Marthe. I looked through every death record with the name Baumann on it between 1870 and 1932. Newspapers can be mistaken sometimes, and famous names can be stolen. There were two Marthe Baumans who died towards the end of the 19th century in Paris, one in 1884 and another in 1890, but when I pulled up the full records, both turned out to be children younger than four. I kept going, searching through the death lists of each of the twenty arrondissements for each decade, combing through exactly one hundred different ledger books until, when I came to the very last feasible decade, in the very last arrondissement, the 20th, I found this: Marthe Baumann, died January 17th, 1923.

“Marthe Aguillon,” by Charles Reutlinger. Musée Carnavalet (source).

Screengrab from the table décennale of the 20th arrondissement for the decade of 1923-1932, (source). Photo by me.

However, to my great frustration, when I went to find the death of this Marthe Baumann in the record book for 1923, it was nowhere to be found. Knowing that sometimes records can be misplaced, and the reporting of deaths delayed, I looked at every death in the 20th arrondissement for six months after the listed date, and for more than two months before. But I found nothing. The records were a mess, all out of order due to the judgements coming down on the deaths of the missing soldiers of World War I several years before, only now being pronounced legally dead so that their parents could collect compensation and their widows could remarry.

There is no guarantee that the record is a match. She might have died in Belgium, struck down by a heart attack after a performance at the age of 69. Or she might have caught pneumonia in Moscow, or the flu in Louisiana, having emigrated and bought herself a house on the bayou. Anything is possible.

If this is our Marthe Baumann, the details do make sense. She would have been quite old—93 or thereabouts—but that was not unheard of for women of her stature. The 20th arrondissement, Belleville in the Roaring Twenties, might have been a fitting place for a famous former actress to have chosen to retire. Until the restrictions for Covid can allow me an in-person visit to the civil archives to get further assistance, I won’t know for certain that this is her. But at least for now, I’d like to imagine that it is. That she lived to a ripe old age, still in possession of some of her silks and furs, still able to enjoy the dawn of the Jazz Age, as the music from the dance halls of her quartier seeped up through the floorboards, put a sparkle in her light eyes once again, and set her old feet tapping.

I will keep you posted.

***

To subscribe to the Book of the Courtesan series, sign up here on Substack.

*************************

REFERENCES & LINKS:

Dictionnaire Général de Biographie et d'Histoire, by Charles Dezobry, 1889, p. 1,494 (link)

Grand Dictionnaire Universel du XIXe Siècle, by Pierre Larousse, 1875, p. 20 (link)

"THÉATRES A VOL D'OISEAU," La Causerie, 28 April 1861 (link)

"Les Coulisses," Le Figaro, 19 April 1863 (link)

"Chronique," La Comédie, 11 October 1863 (link)

"Chronique," La Comédie, 18 October 1863 (link)

"Devant et derrière le rideau," La Comédie, March 1863 (link)

"Devant et derrière le rideau," La Comédie, 12 April 1863 (link)

"Devant et derrière le rideau," La Comédie, 23 April 1863 (link)

"Chronique," La Comédie, 12 July 1863 (link)

"Le Théatre Beaumarchais," La Comédie, 14 February 1864 (link)

"Devant et derrière le rideau," La Comédie, 6 March 1864 (link)

"Theatres," Journal Pour Toutes, October 1864 (link)

"Courrier," La Comédie, 16 October 1864 (link)

"A TRAVERS PARIS," Le Figaro, 26 October 1865 (link)

"Chronique Théatrale," Revue Artistique et Littéraire, 1865 (link)

"Feuilleton du Journal l'Europe: mouvement dramatique français," L'Europe, 27 October 1865 (link)

"La Semaine Théatrale," La Presse, 30 October 1865 (link)

"Tirage du Petit Journal," Le Petit Journal, 12 October 1865 (link)

"Coulisses de Théatres," Le Tintamarre, 19 March 1865, (link)

"Chronique Théatrale," Revue Artistique et Littéraire, 1866 (link)

"FAUSSES NOUVELLES," Le Tintamarre, 7 Octover 1866 (link)

"Revue," La Comédie, 1 December 1867 (link)

"De Paris à Bruxelles," La Comédie, 29 December 1867 (link)

"Le Courrier de Lyon à la Gaité," La Comédie, 21 June 1868 (link)

"Revue," La Comédie, 19 January 1868 (link)

"Etranger," La Comédie, 22 March 1868 (link)

"Courrier de Paris," Le Pays, 2 January 1870 (link)

"Courrier de l'Etranger: Brussels," Officiel-Artiste, 19 July 1888 (link)

"Eugène Janvier de la Motte," by Bernard Vassor, Autour de Père Tanguy, 2 February 2007 (link)